I used to be a “Girl in STEM.”

If you had asked me in elementary school what my favorite subject was, I probably would have said “math” – and then told you that I loved robotics. Looking back, my love for being a Girl in STEM – Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math – was strongest when I did not realize how rare it was to be a girl in STEM.

Nationally, Massachusetts Institute of Technology recently reported that “the gender gap in STEM remains significant, with women making up only 28% of the STEM workforce.”

But I didn’t realize this until I was eight, on my first day of robotics camp. I walked into a room full of boys who refused to partner with me – or even let me touch the computer. It was then that I realized that being a “girl in STEM” wasn’t as fun as I thought it was. That was the last STEM camp I did.

In middle school, while I still had an interest in STEM, it was something I was doing less and less outside of class. My last STEM activity was the Friend School’s 8th grade MathCounts team. Once I reached 9th grade, I was more concerned with reporting on the issue of gender gaps in STEM for the Quaker Quill than in being part of the field myself.

At the same time, along with a small cohort of female friends, I have pursued the most challenging math and science tracks Friends has to offer. This was something I did because not only was I good at it, but I also enjoyed it. But I was always convinced I was more of a humanities person. The truth is, though, it’s hard to tease out whether this is something I’ve become because my early experiences in STEM made me feel unwelcome.

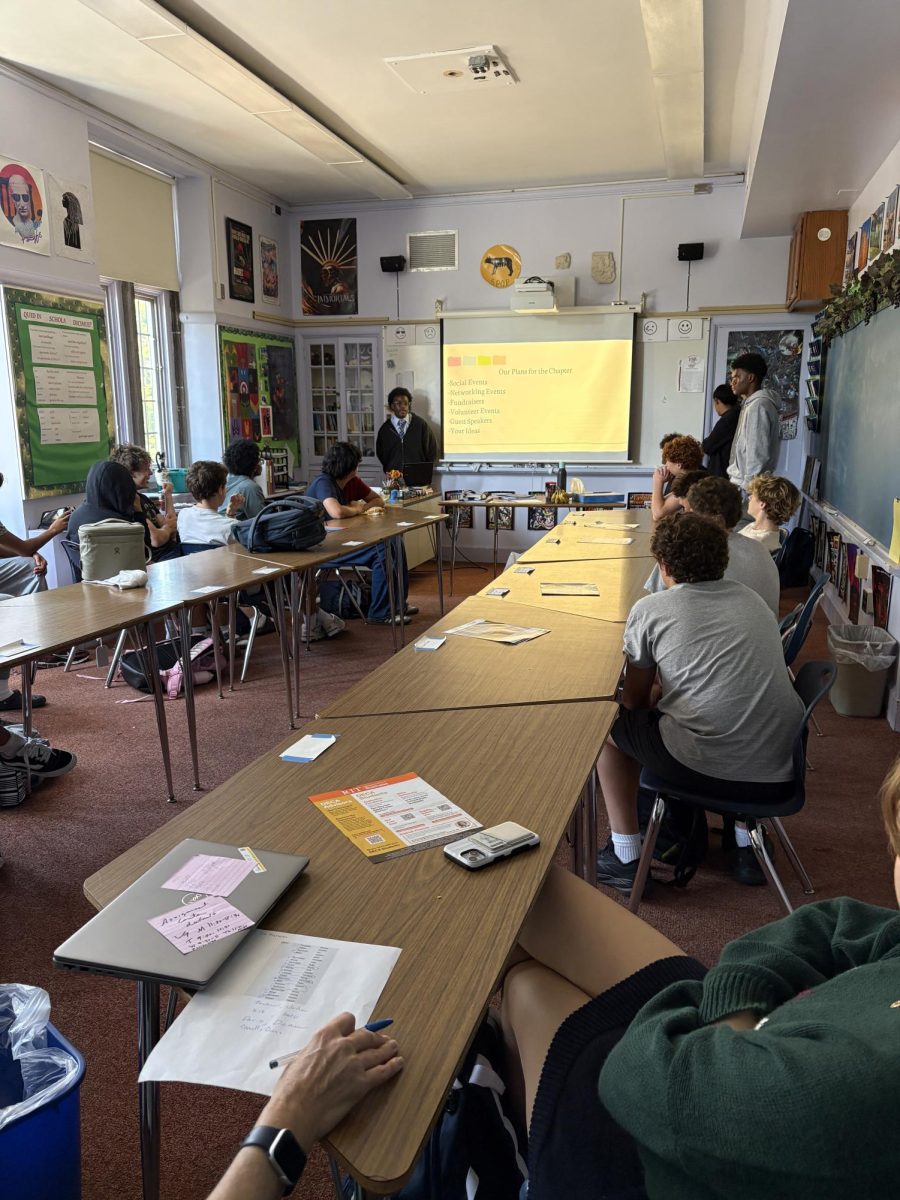

Now, in my last semester of high school, I wanted to revisit the issue of the gender gap at Friends for the Quill, to explore whether much has changed.

I know a few things have. For one thing, the acronym STEAM – adding Arts to the other disciplines – has become prevalent, as institutions recognize common ground between STEM and the arts. For another, more of my peers are using identifiers other than male and female.

But for me, it is hard to see actual concrete changes in the way we encourage all gender minorities to be a part of STEM. And that is what concerns me.

I started by talking with Upper School Physics teacher Vik Polyak.

“I don’t feel as if there has been a big shift. Maybe since we spoke in your freshman year. But it’s hard to describe a pattern,” said Polyak. “I would say that in any given identifier in particular, whether it’s by gender or some other identities, there are people who span the whole range of comfort or skill levels [in STEM classes and clubs at Friends].”

And not just here, Polyak says.

“I know that across our entire society, and not specific to Friends school, there are barriers or hurdles that have to be jumped over,” he says. “There’s not the same level of encouragement for STEM for young women, and for girls and then for people in other marginalized groups as well.”

While American culture, and therefore the school’s culture, towards the gender gap in STEM may not have changed much, Friends School’s science department in general has begun to. Many new female teachers have been hired, such as Hoa Cost and Megan Flora-Quinn teaching Chemistry, and Sophie Kessler and Emily Gibbs in the Math Department.

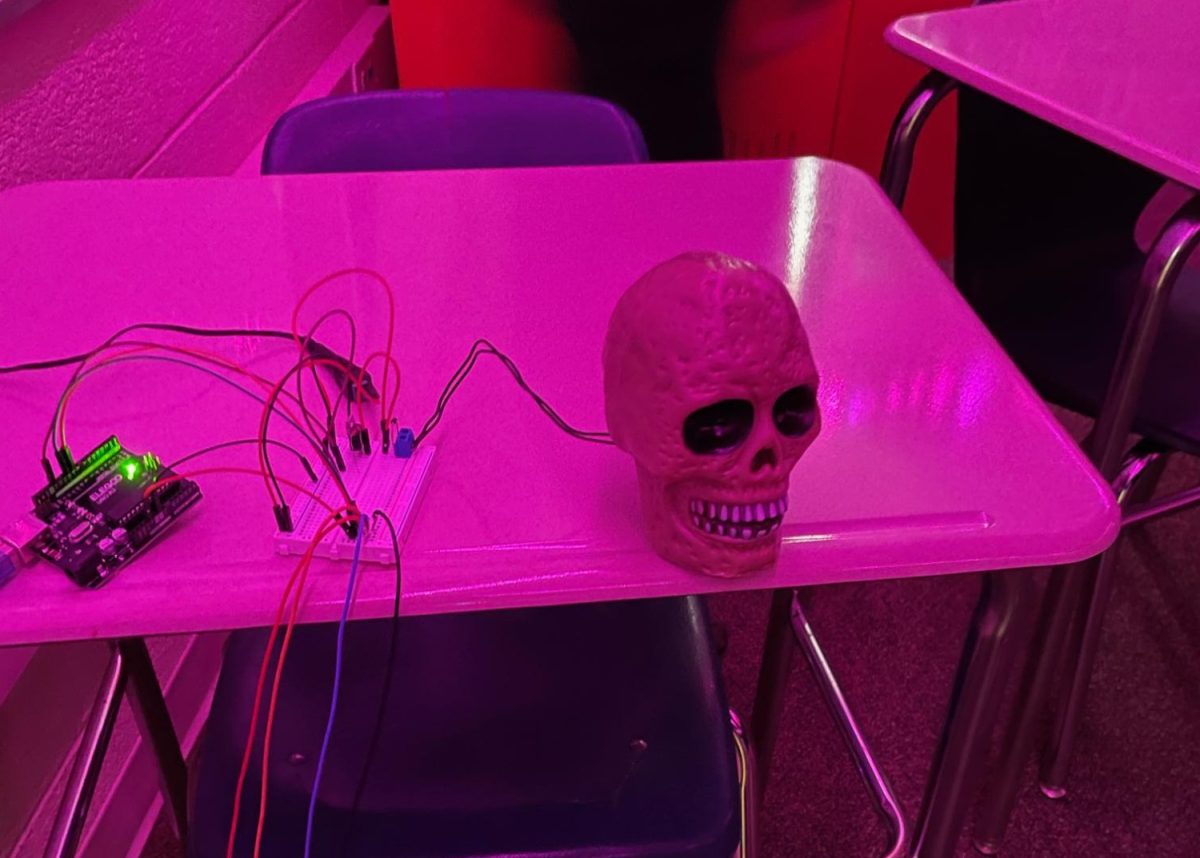

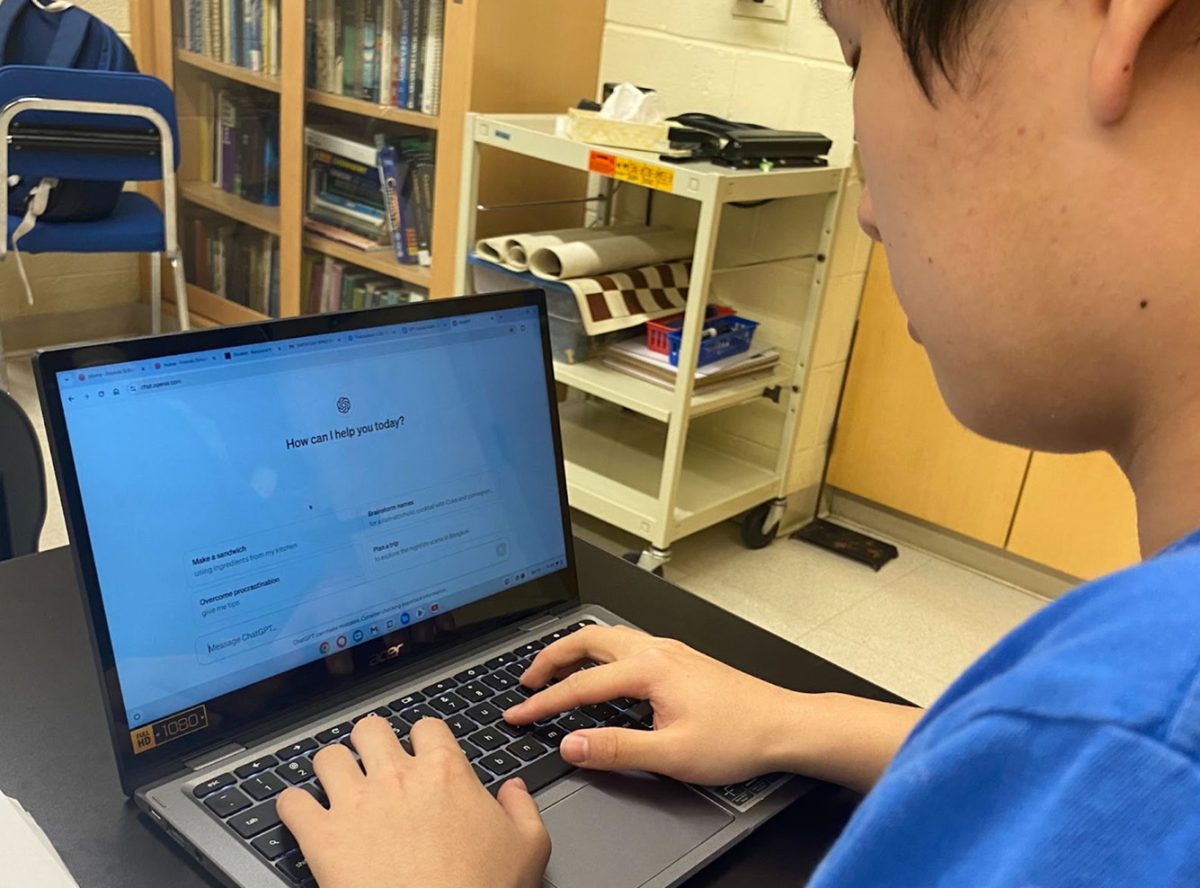

The biggest departmental change has been the new addition of a Computer Science department.

There had been individual computer science classes at Friends for years. But in the summer of 2022, three Upper School teachers – Jennifer Robinson, Head of Library and Technology Studies, along with Computer Science teacher Joel Hammer and art teacher Heather Romney, founded a real Friends Computer Science department. Making their classes as inclusive as possible was one of their top priorities.

“When we were first developing the curriculum, one of the ways that we brought in new computer science courses was we brought them in through art, because we were hopeful that that might attract a wider, more diverse array of students, so that students didn’t just see themselves as “CS” kids,” says Robinson. “Sometimes people have preconceived notions about what that looks like to be involved in STEM-related fields, because it has historically been a male-dominated industry.”

While the new department will hopefully encourage everyone to try out their interests in CS, some of the helpful programs Friends used to have to encourage girls in STEM are gone.

In my previous article, I mentioned that the club “Girls Who Code,” and the STEAM Fair, were highlights in celebrating and encouraging women to join STEAM at Friends. Since then, both activities have become more general. “Girls Who Code” simply morphed into the Programming Club, and the STEAM fair opened to the entire 8th grade class.

Although these changes do technically make the activities more inclusive – especially to other genders, and other marginalized communities – they leave the school with no specific outlets to support underrepresented communities and students in STEM. While it is important to encourage all minorities, many non-male-identifying students feel the loss of these programs, which helped us as we struggled to find our place in STEM classes or clubs.

“In 9th grade when I had Creative Coding where I was the only girl … I felt pretty isolated,” remembers senior Erin Nicolson. “I felt this pressure to keep up with them and make myself feel like I was as good as them, because I was the only girl.”

In that situation, it made a huge difference to Erin to have Romney as her teacher.

“She would make sure that I felt supported, and offer that I join ‘Girls Who Code’ and do the STEAM Fair, because she saw how hard I tried,” says Erin.

While “Girls Who Code” and the STEAM Fair may have changed, Friends teachers’ focus on supporting students like Erin has not. Polyak says he thinks a lot about how best to do that in Physics.

“The first thing that comes to mind for me is trying to make sure that I personally can be welcoming and encouraging to people,” he says. “I try to be mindful of the language I am using and how I interact with people, especially with people who come into class not feeling as if they’re super-powerhouse math and science people.”

Other teachers say they themselves try to be a model for the non-male-identifying students in their classes.

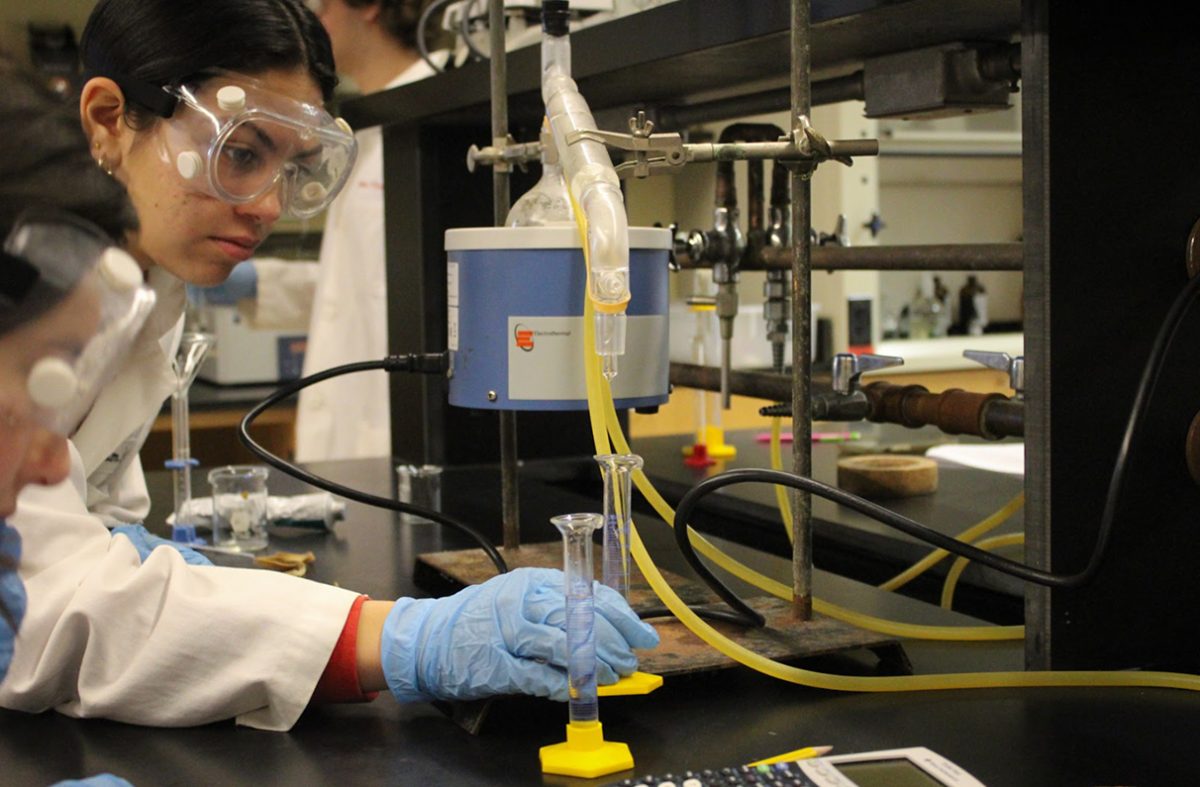

“I try to bring in as much personal experience that I have had, like in grad school or in research and so on, just to try to be that example to the students and have them think in the future about what’s interesting, and what’s possible” says Accelerated and Advanced Chemistry teacher Hoa Cost. “I think being a woman myself and being a minority myself, I think that’s the best way that we can just put in front of the students an example of what we can be.”

Student say this sort of representation has an impact.

“The fact that I’ve only ever had male math teachers at Friends, that’s something that I’ve definitely thought of. I feel like in the highest math classes it’s always a male, and I’ve only had the experience of having a male math teacher,” said senior Audrey Lin, who currently takes the school’s highest-level STEM offerings, Advanced Chemistry and Calc 3. “In middle school and elementary school, all my teachers were women. And then you get to the higher classes, especially in STEM, and it’s much more male-dominated. Other than Dr. Cost. I feel like it’s very empowering to have Dr. Cost.”

I, like Audrey, have not had a female math teacher since 5th grade. Like many, I have not had a direct bad or discriminatory experience in any of my classes at Friends. But the lack of representation can make it hard for students like me to see ourselves pursuing a STEM career.

For girls and other gender minorities who do choose to go into STEM, they are usually very aware of what the future might hold in terms of representation and discrimination.

“Something that I was definitely considering in [my] college [applications] was going to a school where they consider or try to keep up a gender balance in their STEM fields. For example UMD there’s pretty much a 70:30, whereas the schools I really want to go to try to keep it more even,” said senior Suwen Ren, who hopes to major in Computer Science. “So if I study STEM in an environment where I’ll know I’ll be supported and not surrounded by men, I think it’ll be good.”

As I’ve realized through my experiences and creating this article series, it can be hard to pinpoint what causes a lack of women in STEM. From the ‘bro culture’ that Polyak and I discussed, to representation like Audrey mentioned, countless societal factors could impact a young woman in a STEM environment. But there could also just be a lack of opportunities or interest in general. A lot depends on the individual.

I walk away with more questions than answers. How can we truly ensure that we’re doing “enough” to encourage women in STEM – or in any male-dominated field? What even is “enough”?

But, I know two things as I walk away from this series. First, we are trying, at Friends and in the world, to encourage young women to join STEM classes and fields.

And, second, I used to be a Girl in STEM. Going forward, I plan to attend Johns Hopkins University and major in International Studies – not a STEM field, yet still a predominantly male-dominated one. I still work hard in my Multivariable Calculus class. But while I used to be a Girl in STEM, I, like many other young girls, don’t see myself that way now.

![How Freestyle Club Began [Podcast]](https://thequakerquill.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/charly-alvarez-Jv9untmB7G4-unsplash-1200x800.jpg)

![What makes you feel good about yourself? [Podcast]](https://thequakerquill.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/madison-oren-uGP_6CAD-14-unsplash-1200x800.jpg)

![A Phone Ban at Friends? [Podcast]](https://thequakerquill.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/magenta-VrRT19_ZjUY-unsplash-1200x900.jpg)