It’s strange to walk around Bryn Mawr’s campus this year, and not see groups of friends standing together, each girl on her phone. Students can’t walk to class glued to a cell phone screen or listening to music. Phones are absent from pockets, classes, and conversations.

After turning in their phones to a common area each morning, students at Baltimore’s Bryn Mawr School retrieve them at the end of the day. Though the space is large, the wait can be long and chaotic.

Upper School Head Emily Fetting decided to ban phones for high schoolers at the independent school this year. They are no longer allowed, even during free periods.

“For us, it was less about responding to a problem in the classroom and more about concerns that we had about student mental health and wellbeing and the way that we think cell phones have negatively affected our ability to engage in community with each other,” she said.

Phone policies have been a contentious issue across Baltimore private schools this year. Roland Park Country School, Gilman School, and Bryn Mawr all phased in phone bans this winter – and the pilots have been bumpy. The Boys’ Latin School of Maryland has already gone phone-free.

Amid these changes, Friends School of Baltimore is trying to figure out what its phone policy will look like next year. This afternoon, at the April 9th Upper School faculty meeting, the Cell Phone Policy Committee plans to ask teachers to approve a proposal to make Friends a “phone-free school” starting next fall. A majority of students who responded to a recent Senate survey said they oppose the prospect. As teachers discuss the issue, the successes and failures of other local private schools will be on everyone’s minds.

Bryn Mawr, RPCS, and Gilman

Last summer, Bryn Mawr head Fetting started researching the benefits of phone-free schools after hearing at a conference about another girls’ school’s positive experience going phone-free.

She also read The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt, which argues that smartphones and social media are contributing to a rise in mental illness. Haidt’s absolutist stance against technology has garnered mixed reviews. (See here and here.) His critics point out that while social media can impact teens’ mental health, there is not sufficient evidence to show direct links between the two. They also argue that the book neglects other reasons why teenage mental health is suffering.

Still, the connections Haidt explores between phone use and mental illness were compelling to Fetting. They prompted her to meet with school leaders from Bryn Mawr, and its partner boys’ school, Gilman.

“Our thinking was and is if students can store their phones for the day… and not have them as a distraction or something that is taking their time and attention, then we hope they will be more engaged with their peers, with their teachers, and in school life,” she explained in an interview.

Fetting said she believes that improved well-being, more community engagement, and greater focus during class will result from a phone-free school.

Yet educators must navigate significant logistical hurdles to achieve a functional policy. And they must consider how to preserve the trust of the community while taking away students’ personal devices.

Among Baltimore’s local private schools, the Tri-Schools—Bryn Mawr, RPCS, and Gilman—have opted for a phased-in approach to their phone bans. The idea is to iron out collection methods, and how to handle late arrivals or early dismissals, before going fully phone-free.

The rollout also gives students time to adjust. At the beginning of this year, students and families were informed that the schools would slowly transition to a phone ban by the second semester.

Bryn Mawr announced the school’s new policy during a town hall in August, and had another with students at the end of October. They also hosted a parent meeting in November.

“[We] wanted to do it as quickly as we could, but as carefully as we could,” Fetting said about the plan. Her school and its partners started with phone-free Fridays in October. In December, the three schools piloted phone-free weeks to “work out the kinks.” By mid-January, the policy took full effect.

Bryn Mawr is still figuring out how to store and distribute phones. Initially, students turned in phones to an administrator by grade to store in their office. But those adults weren’t always available when students needed their phones’ back. Now phones are placed in one collective room, but students may have to wait to retrieve them.

At Gilman, students can store their phones in their lockers. If they don’t comply, teachers will give them a warning and direct them to put their phones in their lockers.

One day this fall, Brody Carr, a sophomore, needed to let his dad know his lacrosse practice had changed. He could email his dad—even text him on his MacBook. But he says not being able to call and explain was frustrating.

A senior at Bryn Mawr, who asked to be anonymous in order to speak freely, says she has frustrations of her own.

“It makes it seem like they don’t trust the student body at all,” she said.

The student says she believes communicating with parents is hard without phones because they are a “quick and easy” method of communication. She also noted that “it is inefficient” for seniors with off-campus privileges to turn in their phone and retrieve it every time they move on and off campus.

“Phones make our lives so much easier in so many ways,” she said.

Her main concern is that Bryn Mawr has presented the phone ban as a solution to heightened anxiety in school and the classroom.

“If that’s the problem,” she said, “the real solution is completely banning any social media, not only taking phones.”

Most of the time kids use social media and phones at home, not at school, she argued. She said that being able to vote and drive, but not have her phone, “makes me feel like a baby.”

Based on conversations with four students at Bryn Mawr, Gilman, and RPCS, they say there is a mix of students who like the policy, don’t care, or are staunchly opposed to it.

“Some people don’t want to get off their phone. They act like they have self-control but they really don’t,” Brody said. While some kids try to keep their phones in their bags, many kids don’t mind the policy. Despite some frustrations, Brody says the phone ban is “a good policy to have because you really don’t need to be spending time on your phone.”

Fetting says she has also seen students who both like and dislike the policy.

“I’m pleasantly surprised by the number of students who tell me that it’s not a big deal for them,” Fetting said. But she worries about “the real distress that I see from some students because that suggests to me that maybe there’s some kind of unhealthy relationship with a phone.” Bryn Mawr is gathering student’s self-reported data about mental health and well-being, and Fetting said she is hopeful that, eventually, the school will see an uptick in feelings of belonging and inclusion.

Boys’ Latin

At Boys’ Latin, the fall semester began with a total phone ban.

“Everyone has been super supportive of us having the boys’ phones,” reported Amy Wesloski, Head of the Upper School. Despite students’ initial quibbles, she says, the change has been a positive one.

“We’re giving students an opportunity to say, I can’t be on my phone. And it’s not their choice, but I think all in all they really do enjoy it,” said Wesloski, citing the overwhelmingly positive feedback she has received so far.

Initially, she says, she “struggled with: ‘Should they have it on their person and off and away, or should it really just not be with them at all?’ I was thinking about my seniors, you know. I have kids going to huge universities next year, and what am I doing if I’m taking the phone, right?”

Yet The Anxious Generation moved her as well. In the summer of 2024, all Boys’ Latin faculty and administrators read the book, and held a book club to discuss it.

Wesloski learned that “your phone’s proximity to you makes you more anxious, makes you more distracted.”

Doing further reading on the research around teens and phone use, she discovered that kids receive on average 240 notifications a day on their phones.

“If I can shut that down for eight hours a day, I think that’s pretty awesome,” she said.

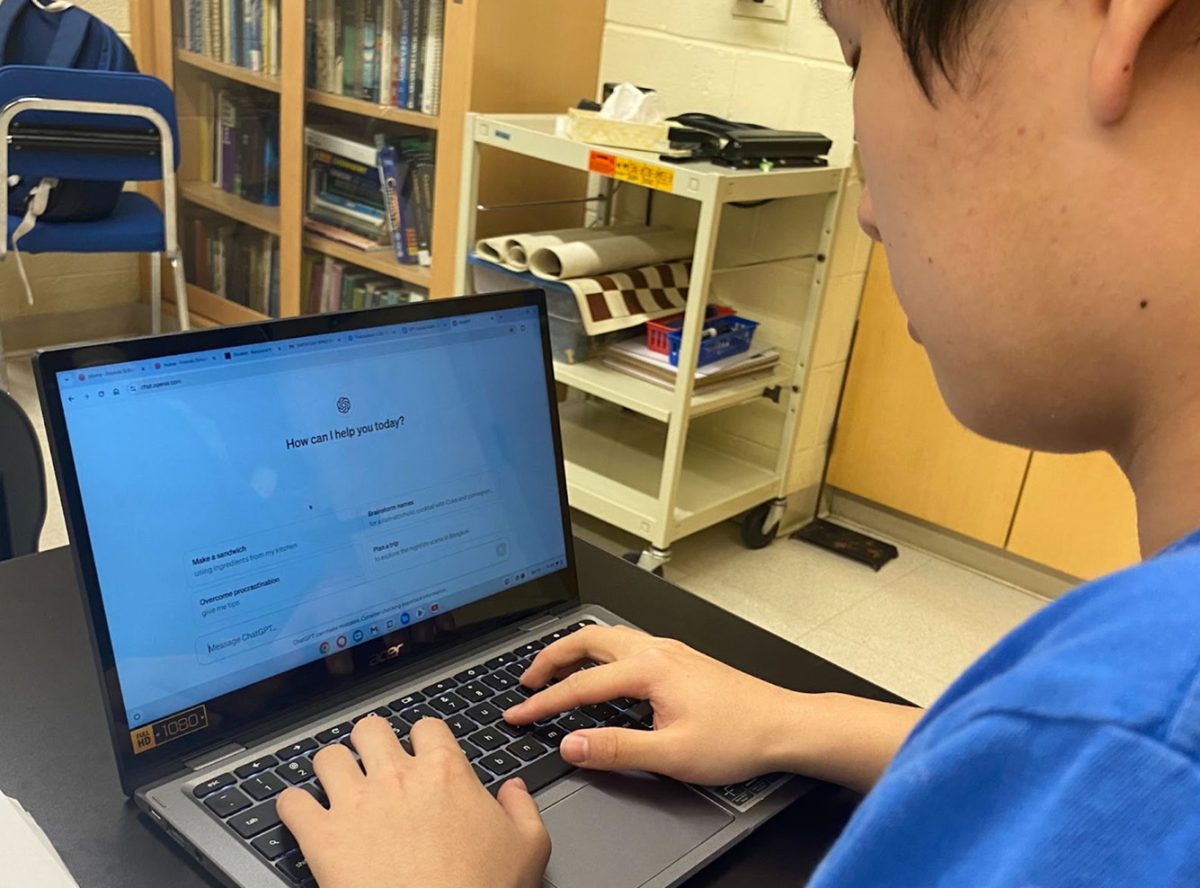

Boys Latin has also banned social media on school computers to reduce distractions and improve mental health among students.

“Normally what might be kids on their phone at lunch, [now] everyone’s talking at their tables,” said Wesloski. Her first day back at school this fall, she remembers it sounded like there was so much noise in the halls compared to the previous spring because the boys were actually talking to one another.

“The boys were going outside and they’re playing frisbee, they’re playing spikeball. They’re, you know, sitting in advisories playing games,” she said.

Yet, starting the school year with such a drastic change, Weloski expected some student pushback.

“I anticipated a little bit more grumbling from the students when we first did it, but there really wasn’t. Or they would do that in front of their peers, but then privately they would be like, ‘This is really fantastic’,” she said.

Boys’ Latin student Jared Forchheimer said he agrees that the policy makes school more authentic, and everyone seems to like it.

Boys Latin has a slightly different collection process than Bryn Mawr and Gilman. Students drop off their phones during advisory in the morning and retrieve them in the afternoon. This prevents long lines, allows the students to check in with their advisors, and makes it easy to enforce that all students turn in their phones.

“I think schools, you know, I think we’re putting too much thought into how this needs to happen,” Wesloski said. “Maybe we just need to do it.”

Friends School

“Just do it” has never been the decision-making process at Friends School. For example, it took years of faculty and student discussions to arrive at the school’s current dress code.

“I personally am very much interested in making sure that we use a Quaker process. I do feel like there is pressure [to move quickly]. But I know that when we rush decisions that they don’t, that’s just not how our community makes decisions,” said Travis Henschen, Upper School Assistant Principal.

Right now, Henschen is heading a committee that started meeting in October to consider the school’s phone policy and whether it’s time for a ban. As part of their research, committee members visited two neighboring schools now collecting phones – Bryn Mawr and Calvert School – to see firsthand how their policies were working.

This afternoon, the Upper School faculty will meet to consider the committee’s recommendation to ban phones in the Friends’ upper and middle schools starting in the 2025-2026 school year.

In a Senate survey of Upper School students in February, 128 of the 167 responders answered “No” or the equivalent to the question “Are you in favor of further restricting the use of phones during the school day?”

The Upper School’s existing policy requires that phones are collected in bins or pouches during classes and community time. Students are free to use them during lunch, free periods, and all other times of day. In the Middle School, student phones must be “off and away,” which translates to in backpacks and in silent mode.

Although Henschen said he believes “students think it’s a pretty reasonable balance,” he says “what we need to explore together as a community is, do we want to go further?”

Part of the impetus for Friends reconsidering its policy was a talk by Jared Horvath, the neuroscientist who spoke during Collection last year. Horvath came back to campus to talk to teachers and administrators during opening meetings in August. He raised points about how technology affects learning. For example, students don’t retain as much information when they type as opposed to writing. When teachers asked about whether science supported a phone ban, Horvath firmly said it would be beneficial for students.

Henschen agrees. He says even he sometimes struggles to get off his phone.

“For me, it’s a health issue. It’s a wellness issue,” he said.

Henschen also has a greater interest in how Friends can manage the impacts of technology as a whole on the community, including computers.

“To me,” he said, “it’s just as important to address the learning about this so that when you all head off into adult life, you’ve gone through some kind of self-reflection about: ‘What is my relationship with my phone? What do I want my relationship with technology to be? How is it impacting my health?’ Instead of just like, ‘Well, I couldn’t have it in school and then I just use it 10 hours at night.’ Is that better?”

Henschen is not the only person making this decision. The 15-member committee he heads includes representatives from the upper and middle schools, from technology enthusiasts to self-described phone haters.

Henschen emphasizes that in deciding what to recommend to the faculty, the group has taken into account both student and parent input. So while the decision will ultimately be made by adults, community feedback is important.

“I have friends who are administrators at different types of schools and they’re like: ‘Well, why can’t you just do it?’ And I’m like: ‘Oh, no, no, no. That’s not how it works,’ ” Henschen said, laughing. “That isn’t the type of community that we’ve created. We have to actually explain why something is the way it is, and then it’s much easier to implement.”

By considering a phone policy later than other private schools, Friends is trying to learn from their struggles and build a policy that works for this community.

“I am excited to see what solutions come up, because [we] shouldn’t go into it having an outcome in mind,” he said. “We have a trusting community, and that is really difficult to achieve. So how we approach these things really matters. The process really matters.”

On March 5th, the phone committee presented their findings at the Upper School Faculty Meeting, and asked teachers to support a “phone-free school” for next year. Their proposed implementation strategies included the possibilities of collecting phones in morning Advisory meetings, first period classes, the Main Office, and Yonder pouches.

The faculty did not come to a consensus, so as Quaker process dictates, the question was held over until today. This afternoon, the group may achieve a “sense of the Meeting” and move forward with a decision – or might need to keep talking about it.

![A Phone Ban at Friends? [Podcast]](https://thequakerquill.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/magenta-VrRT19_ZjUY-unsplash-1200x900.jpg)