On November 30, 2022, the non-profit OpenAI released its first rendition of ChatGPT to the public. According to Exploding Topics, the web app has amassed an average of 1.6 billion visits a month since its launch.

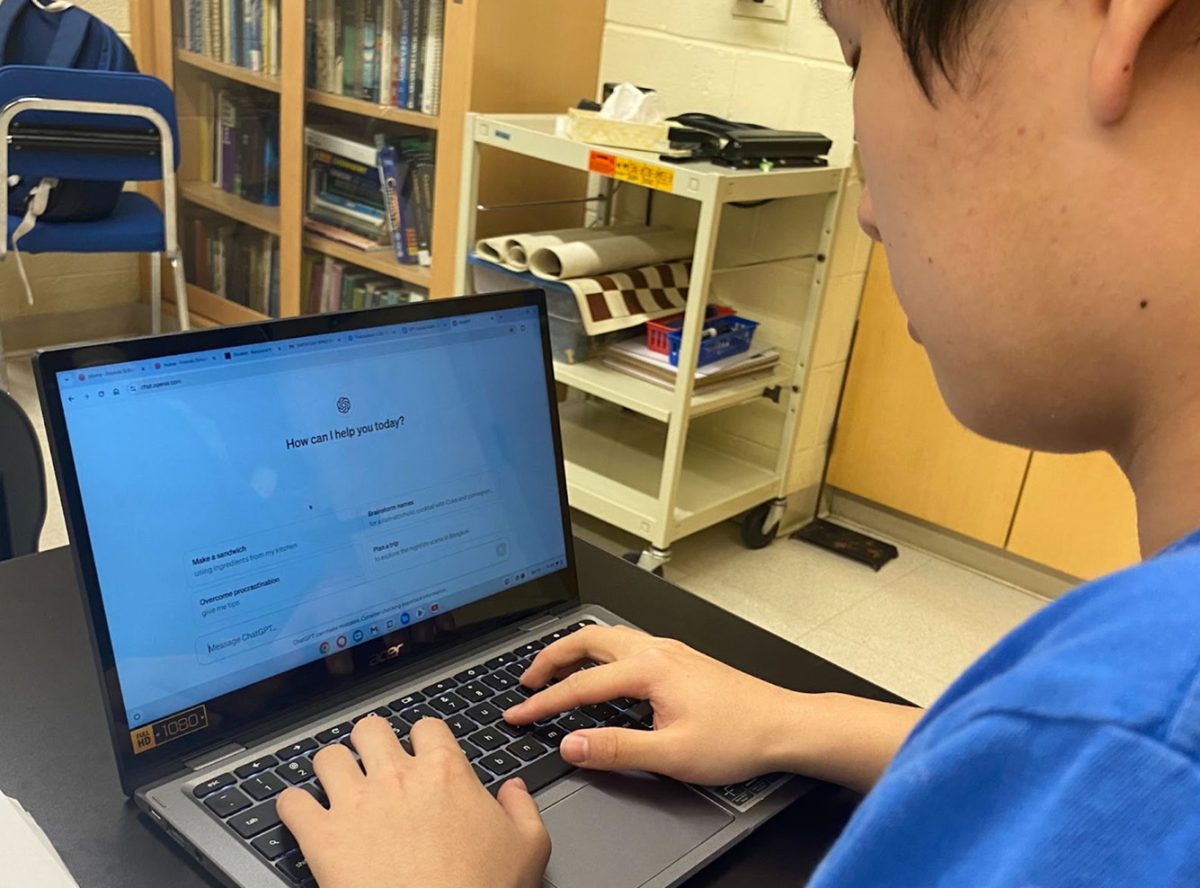

As use of ChatGPT becomes prevalent in schools across the globe, more mixed opinions arise on its efficacy and morality. At Friends School of Baltimore, ChatGPT is being used by both high school students and teachers. Controversy has arisen as a result of its uptick in use, and Friends School community members have a wide variety of opinions on the matter.

“The way AI seems to be working now, it almost is like a person writing stuff. I would view it now almost like a friend helping you revise something,” says Senior Isaac Apencha. “I also don’t agree that you should use your friend to write something for you. Thinking of it as a friend, it’s easier for people to create those boundaries in their own mind.”

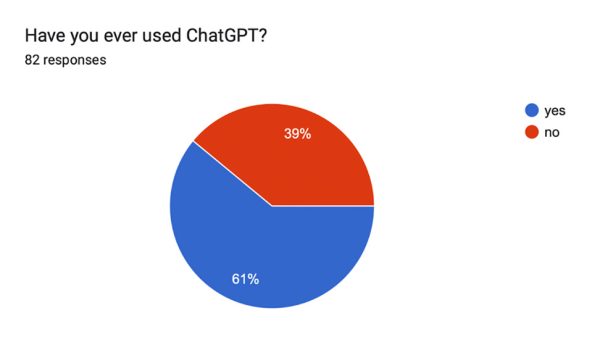

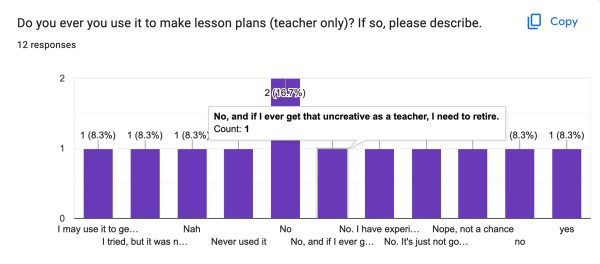

A recent Quaker Quill survey of the Upper School about individual ChatGPT use yielded 82 anonymous responses. Of the responders, 90.4% were students and 9.6% were teachers. 61% percent of responders claimed to have used ChatGPT, while 39% said they had not.

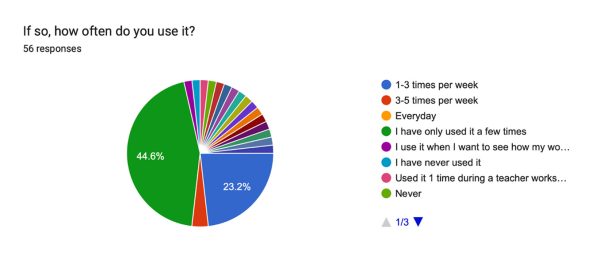

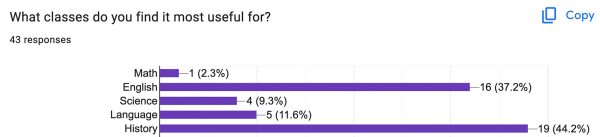

Of those who use ChatGPT, 44% said they don’t use it on a consistent basis, 23.2% said they use it 1-3 times per week, and 3.6% claim to use it 3-5 times per week. Of the 43 people who responded to an optional question about what class they find it most useful for, 44.2% answered history, 37.2% English, 11.6% language, 9.3% science, 2.3% math, and the rest indicated “other.”

While this dataset is not representative of the entire Upper School, it reveals some existing trends. First, ChatGPT use exists at Friends School. Second, students are using it primarily in writing-heavy classes.

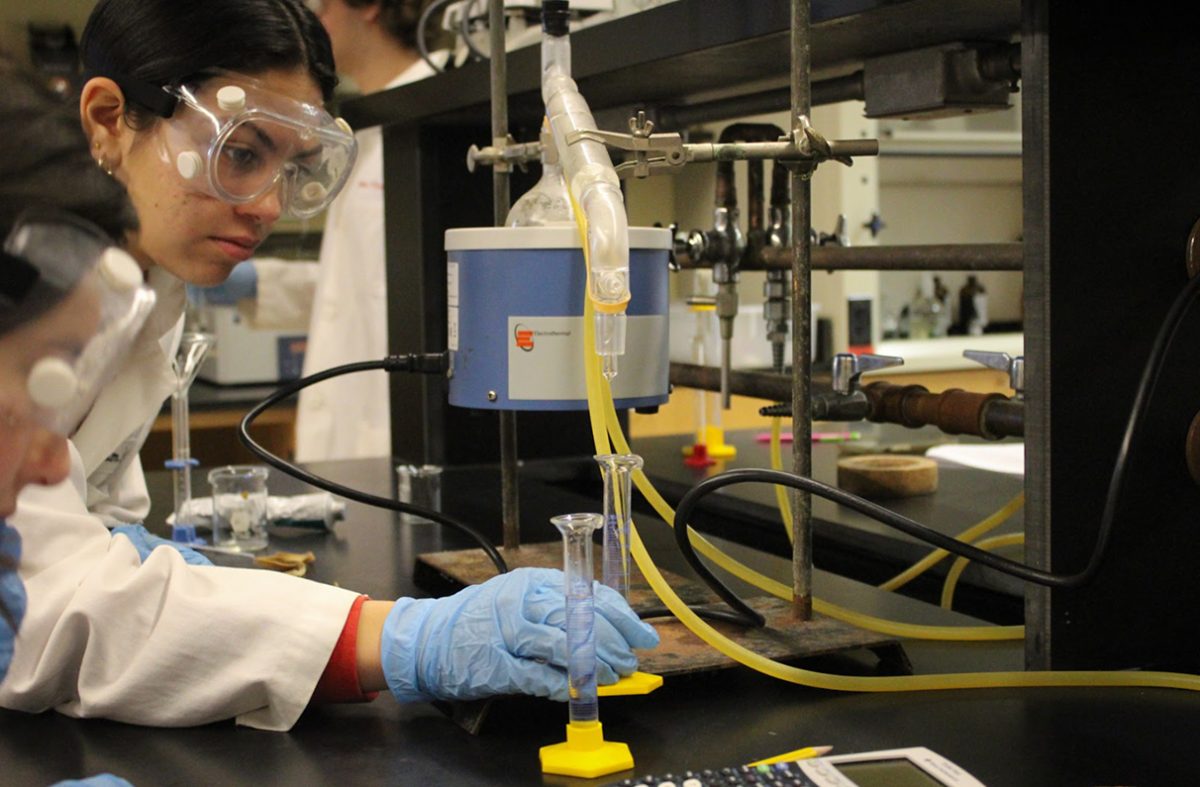

In the wider world, the main fronts in the generative AI debate are its practical and moral implications. Here at Friends, the junior research paper provides a specific and relevant context on which to discuss real-world ChatGPT applications.

In this project, juniors are tasked with deep reading, note-taking, and analysis.

Molly Smith, an Upper School History teacher who oversees much of the research paper process, was part of a Friends summer GROW cohort that spent a week last summer researching AI tools such as ChatGPT. At the time, she did not find it capable of producing useful answers to prompts. And she says she can imagine limited student uses of it being fine.

“I think to get general ideas, I don’t see a problem,” she says.

But when it comes to more specific uses, she recognizes the risks it poses to student learning.

“If you are given a reading and you are supposed to take notes on it and you just scan it into ChatGPT to get notes, you haven’t learned anything,” she says.

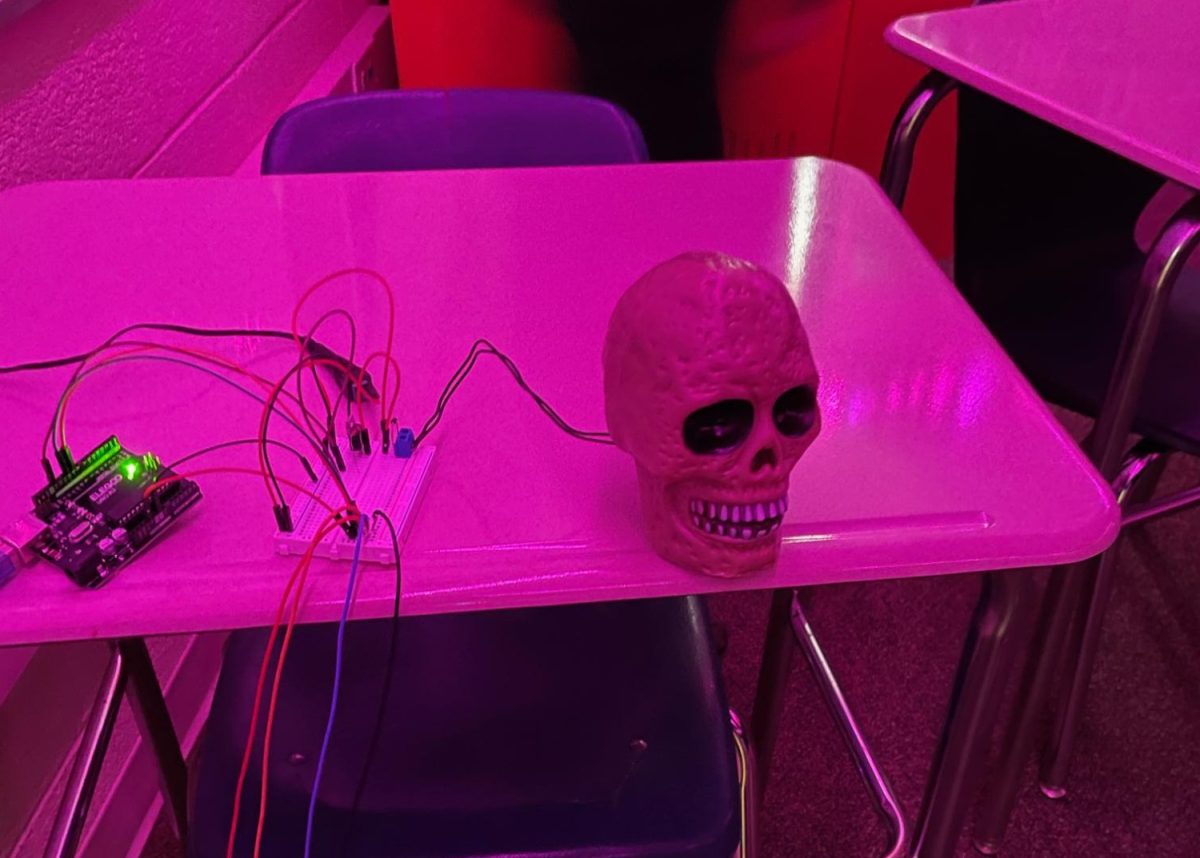

Academic shortcuts are as old as academia. In the internet age, they have long existed in other forms, like Google searching and surfing sources to find an answer. But ChatGPT has significantly expedited this process by providing in-depth responses to niche questions in seconds.

The tool’s ability to respond quickly has prompted questions about whether ChatGPT is more efficient and effective for learning, or whether it oversimplifies the learning process and causes excessive user reliance. Upper School students who agreed to be interviewed on condition of anonymity spoke about their ChatGPT use.

One junior uses it primarily to synthesize readings when in a time crunch.

“I use it sometimes to summarize my English or to rephrase something or take notes on history when I don’t have much time,” they say.

Another junior says they view it almost like they would getting insight from friends or teachers.

“When I have to write an essay or paper and I want to get some ideas, different viewpoints I may not have thought of to begin with, [I use it] just to get some input,” they say.

Upper School math teacher Jordan Wright says teachers have a role to play in prompting students to think about why they’re using the technology.

“[We] need to ask students, ‘What’s your goal of using ChatGPT in an academic setting?’ Are you trying to explore some things and get some ideas? Or is it like: ‘It’s 11 o’clock at night, [my] paper is due at midnight, and I need something?’ ”

Friends PreK-8 Principal Heidi Hutchison was an early adopter of ChatGPT in a professional context. She says she finds its human-like input helpful when crafting work emails.

“Sometimes, if I have a difficult email that I have to respond to, I will write out my response and then ask ChatGPT to take [the] tone out of it,” she says. “It helps me actually see the difference, because when you have an emotional response as a professional you want to take tone out of the email.”

But Hutchison stresses that the writing is still hers – just refined by AI. And that matters, she says.

“When you are a school leader, people want to hear your thoughts and what you think, not what ChatGPT thinks.”

Teaching students how to use the tool could help them, too, become better writers, Hutchison says.

“Give them assignments to use the tool with writing – then ask them to write their own piece, making that even better,” she suggests. “If we don’t start teaching kids how to utilize this tool, it will be abused in different ways.“

Hutchison does stress that ChatGPT use should be limited for Middle School students – whose current handbook bans the use of the technology entirely.

Travis Henschen, Upper School Dean of Student Life, is more skeptical of the technology. He says he approves of limited uses of ChatGPT: for citing sources, fixing small grammatical errors, and other syntactic tasks. But it really depends on the context.

“It’s when you are passing off work as your own and it’s really not your own, is the main area of concern,” he says, “and skipping all those steps of the learning process that the assignment was designed to achieve in the first place.”

While the details of generative AI’s precise use remains contentious, everyone interviewed for this article agreed that the tool has a place in academics. It’s just that what that place is, is still ambiguous.

“We need to start learning how to use it for good, because it’s not going anywhere,” Hutchison concludes.

![A Phone Ban at Friends? [Podcast]](https://thequakerquill.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/magenta-VrRT19_ZjUY-unsplash-1200x900.jpg)

![How Freestyle Club Began [Podcast]](https://thequakerquill.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/charly-alvarez-Jv9untmB7G4-unsplash-1200x800.jpg)