How Friends Financed Pandemic Education

COVID brought with it new expenses, from tents, sanitizer stations, and ventilation systems, to emergency financial aid, tuition refunds, and salaries for employees who couldn’t work.

Friends School photographer Laura Black

In November 2020, students joined Christine Saudek’s ninth grade English class both in-person and over Zoom, under one of the tents Friends purchased to make hybrid learning possible.

October 25, 2021

You know the world is in shambles when multimillion dollar organizations like Friends School scramble to find the funding to cover millions in unexpected expenses.

As the world around us shut down due to the pandemic, schools spent millions of dollars finding ways to continue the education of their students.

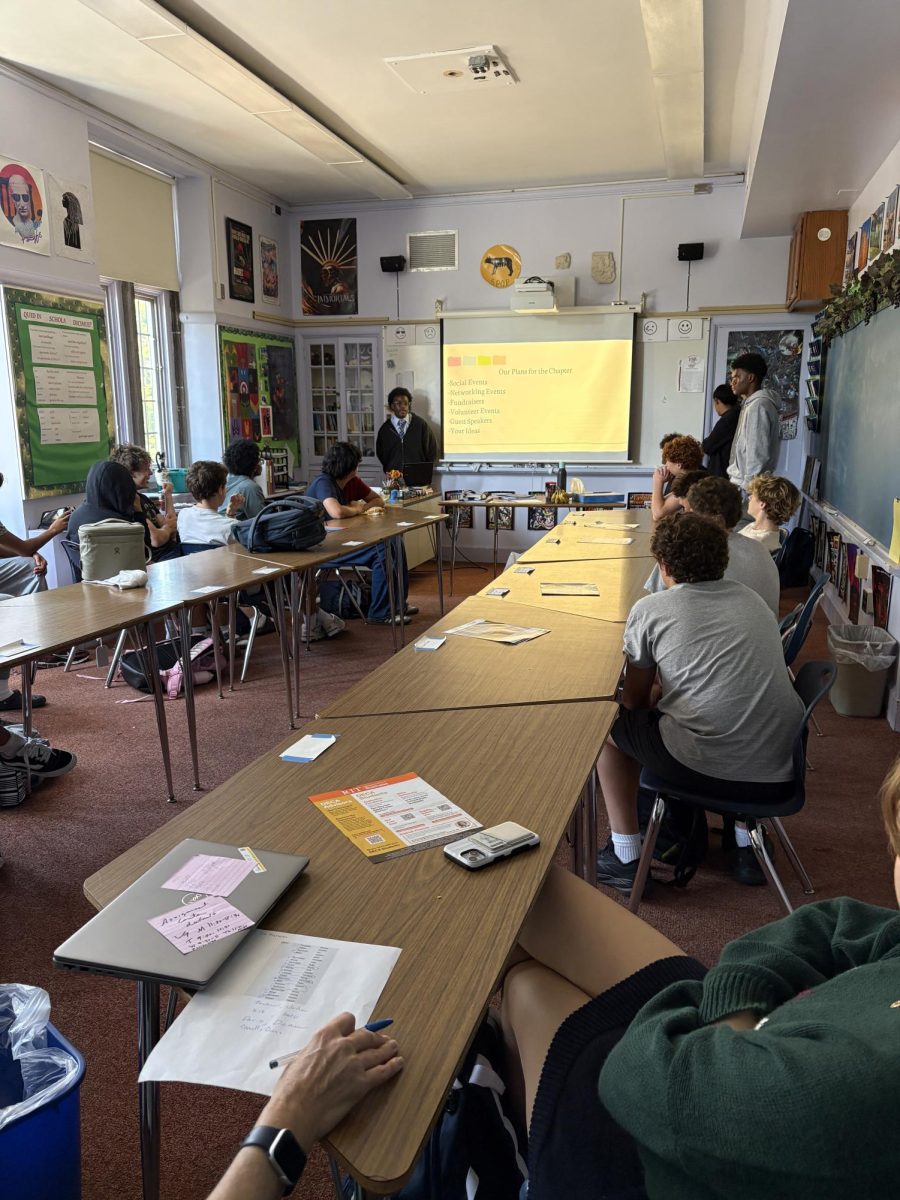

While Friends has navigated COVID these past few years, students have witnessed a lot of changes to their schedules and learning environments. We transitioned multiple times to virtual learning, and went to class in parts of the school that used to be walkways and fields.

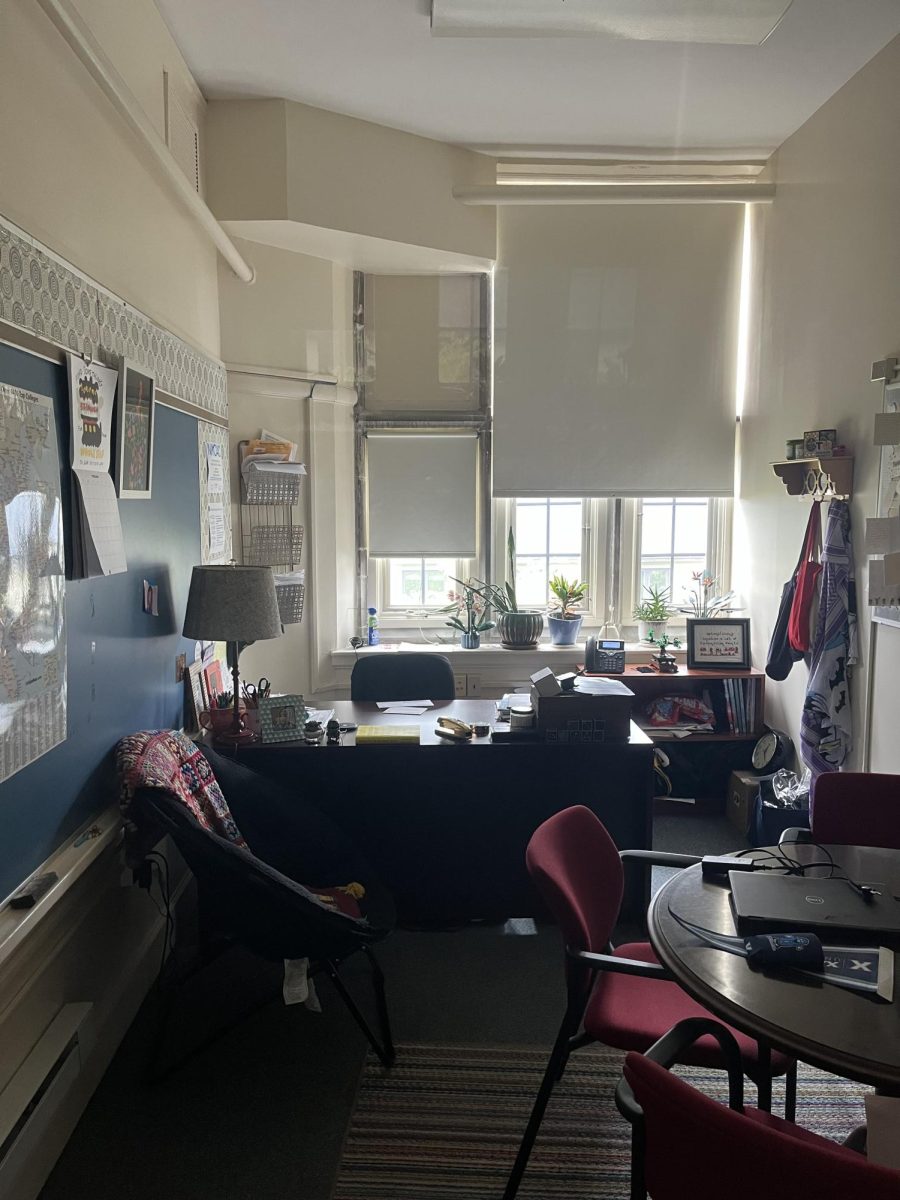

As students and teachers adjusted to these new conditions, Bonnie Hearn, Assistant Head of School for Finance and Operations, Jeanne Phizacklea, Assistant Head of School for Enrollment Management, and others, were working hard to manage the funds that went into these adjustments.

“People understood the goal was to keep people employed and to manage the finances of the school and not have students leave because of financial reasons,” says Ms. Phizacklea.

But that was easier said than done.

“In the big picture we’re really a 25 million dollar organization,” explains Ms. Hearn. “We have 220 employees with lots of seasonal employees. We have 250 thousand square feet of buildings and 34 and a half continuous acres. So there’s a lot to take care of.”

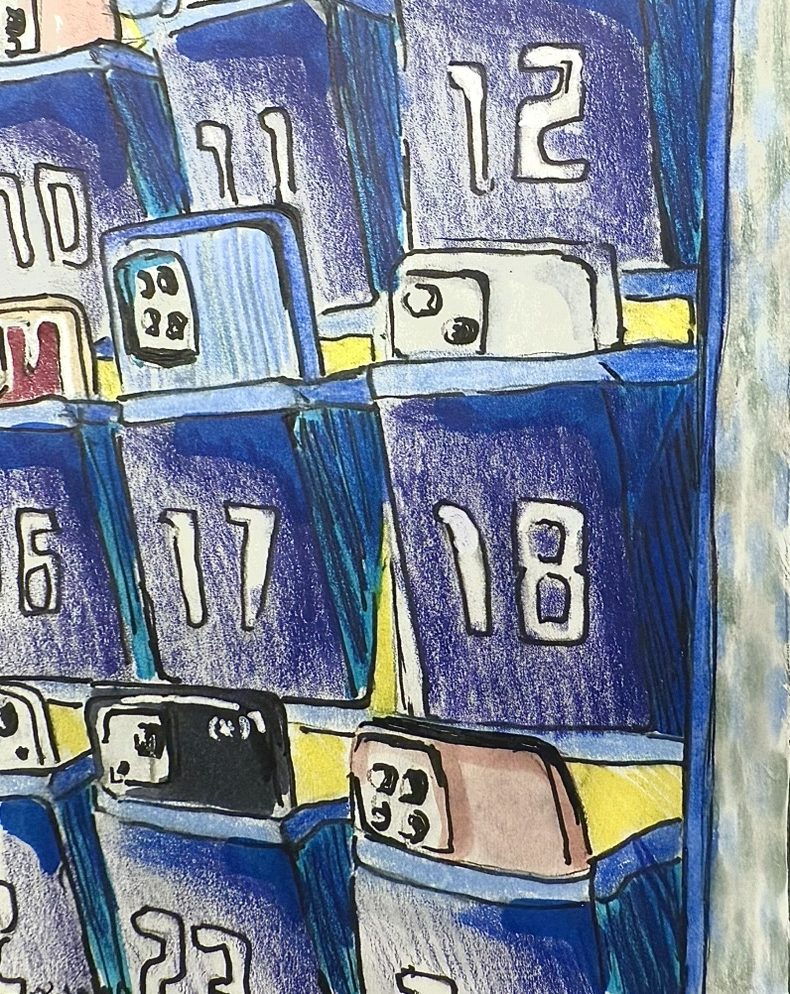

During the 2020-21 school year, the school dealt with expenses that would allow them to bring students back in-person, while in keeping with Center for Disease Control guidelines and ensuring the safety of students, faculty, and staff. They set up hand sanitizer stations, ventilation systems, and other personal protective equipment, which drained over $1.1 million.

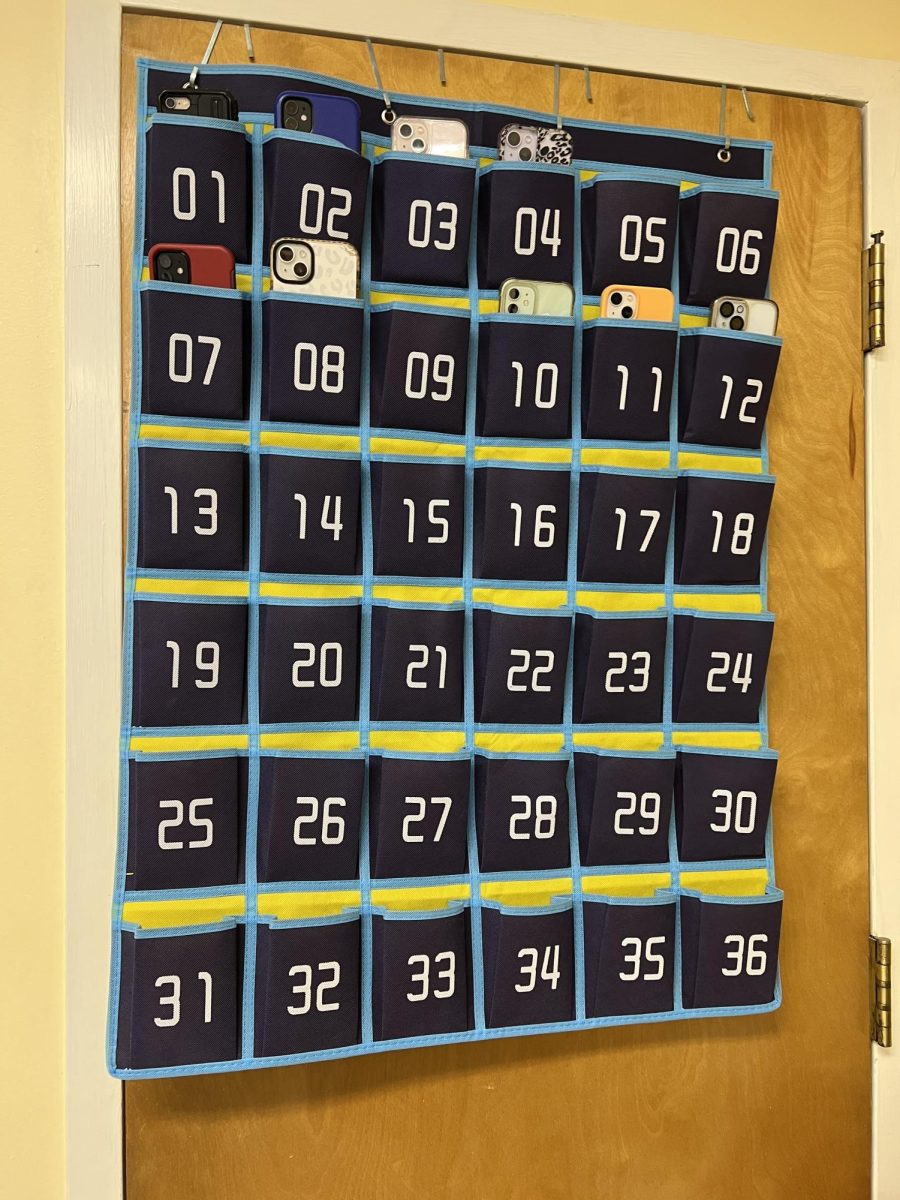

In addition, the school needed to find larger spaces to hold classes so students could be socially distant. So it installed outdoor tents – outfitted with heaters, cameras, and big-screen TVs – to hold classes that some students attended in person, and others (including some teachers) joined over Zoom.

Friends also needed more teachers in the Lower School to help socially distance students, and proctors for teachers who couldn’t come to school for medical reasons. This year, the school is spending $600,000 on additional personnel and a few remaining tents. In each Lower School grade, Friends added a homeroom to allow for more space to socially distance students.

Dennis Bisgaard, Interim Head of School and someone who knows the ins and outs of the American private school system, says that different schools had vastly different expenses, depending on their student bodies and locations.

“You have … some city schools that didn’t necessarily have the capacity to utilize the outdoors and who might not have the appropriate HVAC systems. They could actually have huge expenses to try to get ventilation and air purification onto a campus,” he says. Other schools “have to have more bodies to do the teaching, or you might have teachers at home and someone who’s assisting in class. So they would be doubling their expenses.”

But, he continues, “there were also some expenses that you didn’t have to cover. So you wouldn’t have food services, and transportation was probably different.”

Last year, Mr. Bisgaard worked for a school in Seattle, WA, called the Northwest School. He shared how they managed to maintain a sense of community during the pandemic.

One thing the Northwest School did is that, instead of firing their cooking staff, they distributed lunch to their students around the city. They used the same system to distribute art supplies and books from the library that students needed.

This way, as parents were still paying around the same tuition, students could still take advantage of some of the school’s resources.

Bisgaard says this system was a “pretty amazing community builder, and most parents and guardians … really appreciated that there was still community and food. So it was an interesting approach and [way to] problem-solve”.

Northwest also set up classrooms for students who lived in an environment that wasn’t ideal for learning remotely – for example a small apartment with a lot of other family members working from home. They also made an effort to keep school athletics alive.

“We were pretty much out through March, however, we made sure that there was still athletics the entire year,” Bisgaard says. “We would have small groups of students. You know, there was cross country, basketball with masks on.”

Like the Northwest School, Friends spent money to adapt to this unprecedented situation – including, to help ensure the financial security of faculty and staff, and make sure families were able to stay at the school.

One of the most important expenses the school faced was paying employees who couldn’t work over the pandemic.

“The board felt very strongly that no one not get paid – even teachers at Little Friends who couldn’t work virtually,” Phizacklea says. Many teachers in the pre-primary and Little Friends weren’t able to teach and provide care, which also meant that the school had to relieve parents of tuition.

The school also wanted to ensure that all parents could pay tuition. They knew that the pandemic had worsened people’s finances.

“Philosophically, we’re looking for a school that’s diverse in a lot of different ways,” Phizacklea says. The school knows that not all parents can pay for this type of education and they want to make sure that everyone, no matter where they come from, can pay for this school.

But since the pandemic affected different people in very different ways, they had to make sure they accommodated that.

“We called that emergency tuition assistance, and people had to apply for it. It was either added to their existing award and they needed a little more, [or] for some people, it was the only award they got and it was for one time,” she says. “We gave about $350,000 of additional financial aid because of COVID.”

As a result, the school didn’t lose students because of COVID.

“No one said I can’t do it anymore,” says Phizacklea.

The school ended up with $3.3 million in added expenses.

“It’s not where our revenue decreased, it was where our expenses increased,” says Hearn.

Like many other schools, Friends applied for a PPP loan – money that came from the federal CARES act – to pay for those expenses. The school was eligible for a loan of $3.1 million, which didn’t completely cover its expenses.

“Some of those PPP loans were in the millions, and there was a lot of controversy at some schools,” says Bisgaard. “A school like Sidwell [Friends, in Washington, DC], that have a big endowment and are thought of as quite resourceful, they took the PPP loan, and many other schools did, and decided ‘You know what, we are in a place where we really shouldn’t access money that should serve the larger education system,’ and deliberately didn’t take it.”

Hearn says she believes that “most schools applied for and received some level of funding. I only know of one, actually, in the area that did not apply. And that is because – well, I guess they just didn’t think they were eligible.”

Other than a couple of schools, Hearn says she doesn’t believe any school could survive the pandemic without some level of funding.

In the end, Hearn, Phizacklea, and their team worked together to keep this school alive during the pandemic. At the end of their interview, they sighed with relief at the prospect of the pandemic coming to an end.

“I remember the good old days when we just talked about how much the trash cans cost,” Hearn joked.

“Or what kind of milk to put in the dining hall,” Phizacklea added.

![How Freestyle Club Began [Podcast]](https://thequakerquill.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/charly-alvarez-Jv9untmB7G4-unsplash-1200x800.jpg)

![What makes you feel good about yourself? [Podcast]](https://thequakerquill.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/madison-oren-uGP_6CAD-14-unsplash-1200x800.jpg)

![A Phone Ban at Friends? [Podcast]](https://thequakerquill.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/magenta-VrRT19_ZjUY-unsplash-1200x900.jpg)